I had revelled in the thought of escaping, however briefly, the bustling, dusty and many-faced city of Kathmandu. As a Canadian woman, not raised in a city, my peace of mind has always been in nature, and six months in the overpopulated capital had worn me thin. These trips to Dhankuta had been my golden tickets, my time to escape, my time to explore.

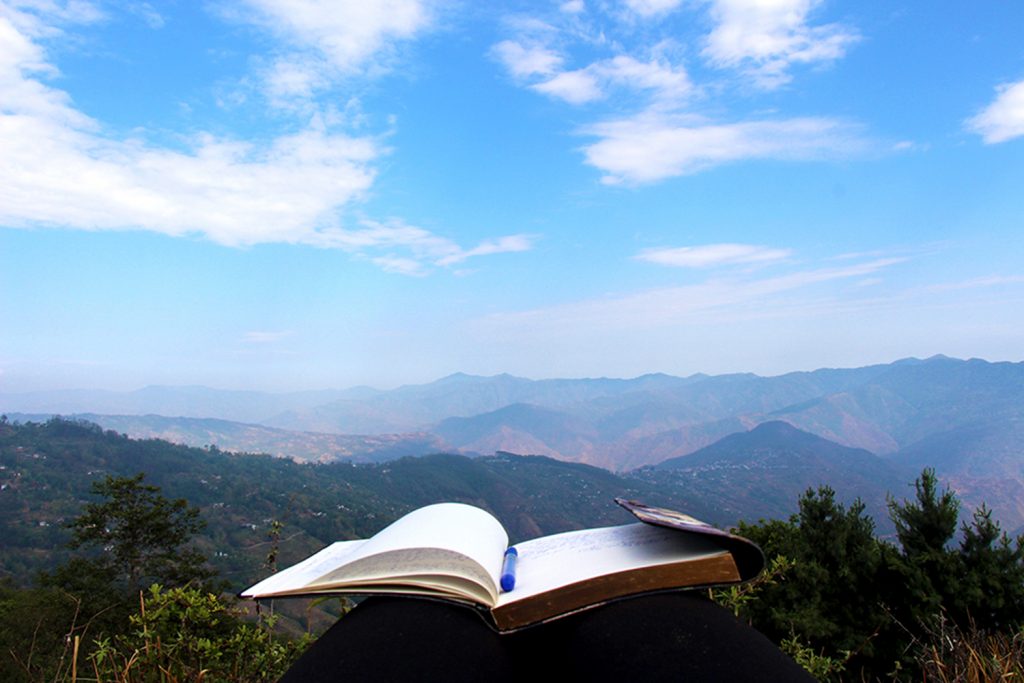

So there I was, at the end of my last visit- two full weeks, albeit for work, to the far Eastern region of Nepal. The trip had done what I had hoped; my spirit had re-awakened in the rolling green hills. During the long days, I would spend hours, when not working, just roaming through the lush jungle like forests, following cattle trails that took me through family farms and up big hills where I could sit on what felt like the edge of the world and find natural silence and wonder.

Foreigners don’t often make it to Dhankuta district; there is simply not as much immediate attraction as you would find in other parts of the country where tourists have blazed their way. Dhankuta, however, is by no means without. I felt fortunate in my time there to be one of the few from outside who have been able to appreciate its beauty. Even Nepali people not from the region rarely venture that way.

I was in all respects remote, and I loved it. Building meaningful connection with the people I met was so much easier than in the city or where tourism prevailed. Time seemed to move slower in the village and moments spent speaking with one another while we sipped chiyaa or watched the cows graze were somehow more precious. In clear weather, with the Himalayas almost mistaken for clouds in the horizon, I would sit on the hillside with didi. Some days, she would point to various homes and huts and tell me the history of her family in a level of Nepali I would never understand. On other days, our conversations simple and unrushed, we would speak about the clouds. This was my Dhankuta, and I was sad to be leaving.

The journey to Dhankuta from Kathmandu had cost me days of travel that spanned from the fast and straight highways of the Terai to the narrow winding roads, which precariously hugged and climbed the foothills of Everest region. The thought of my journey home was daunting. At least on my way to Dhankuta I had arranged transportation with colleagues from work. Getting home would be a totally different story.

The rains were heavy at this time of year. The day I left Dhankuta it was pouring. To stand outside unsheltered would mean being soaked to your skin in ten seconds flat. I found myself crammed in the very back of a minibus fortunate to have a window seat. We were still far from any sizeable village and the bus had stopped. With the rains pouring, I had little visibility out my window. There was a line-up of buses and cars ahead of us, and our driver was speaking to the passengers in Nepali. People began moving to climb out. Still groggy from half dozing and listening to music, I curiously asked my neighbor what the problem was: the road had washed out. Great.

We exited the bus, and I followed the stream of people up the lines of parked vehicles to where a small CAT was fruitlessly attempting to reform the road and block the rushing river that was flowing down the mountain sweeping away any efforts.

Flash flooding is a dangerous and very real risk during the rainy season in many parts of Nepal. In seconds, entire roads and houses can be wiped away as the side of a mountain weakened by erosion, poor infrastructure or earthquake simply gives way. On many occasions, I would hear tragic reports of cars getting washed off the mountainside and families drowning trapped in their vehicles. As a foreigner, it is important to acknowledge and understand the realities of the country you are visiting. Without letting fear be a deterring factor, I choose to remain respectful of conditions for safety, use local knowledge to measure risk, and I adapt. In this situation, I knew one thing was for sure: I would not be in the bus when inevitably the driver tried to cross the river. This is Nepal, and every driver is a cowboy.

Fortunately, the road wasn’t completely gone. I stood on the sidelines not wanting to get involved. It wasn’t my place, and I would have nothing to offer for support. Nepali people are incredibly resilient. I knew this would not stop the traffic crossing and it would be a spectacle. A quiet group of women comfortingly shared their umbrellas with me and together we watched.

First the 4x4 jeeps crossed with little to no pause. If you have the luxury, travel by jeep. Then, the impatient motorcyclists tried to hammer their way through. All were fortunately successful, though some crossings were less graceful than others. I watched one motorcycle drop his passenger in the water.

Next, came the buses. Our minibus was second in line. The bus in front of ours did its best to cross, but without success. It was nearly half way across when its tires began to spin as the rush of the water battered its side. The CAT eventually got involved and pushed it the rest of the way.

Now it was our turn. The bus rushed the river as a few men ran behind. When the bus eventually began to slow, they quickly put their weight behind to help it keep its momentum. Mud was flying and a few unlucky souls got drenched. This time the CAT was ready and it took the place of the men to guide the bus the rest of the way. With the bus barely slowing down, my fellow passengers and myself rushed the moving door. You are not in Nepal if you are not climbing into a moving bus. We were all soaked, but smiling from excitement and success.

The rest of the road home was thankfully clear, and I will never forget Dhankuta.

0 Comments